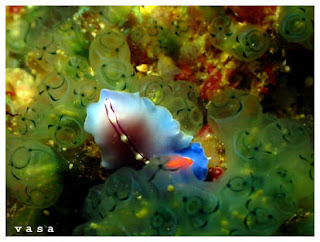

G L A U C U S A T L A N T I C U S

also known as

t h e s e a s l u g, t h e s e a s w a l l o w, b l u e d r a g o n, b l u e s e a s l u g

or the

b l u e g l a u c u s, b l u e o c e a n s l u g, b l u e s w a l l o w s l u g

Phylum: Mollusca

Class: Gastropoda

Body Structure: Sea Swallows grow up to 3-5 cm. They have flattened bodies and six appendages which branch out into attachable cerata which help in respiration. Most have exactly 84 cerata. They have radula with barbed teeth. Their heads contain oral tentacles and rhinophores used to smell/taste food. They have eyes but they can only detect light or dark, they are severely limited compared to our eyes. Most interestingly, they have an anus on the side of their bodies. They have stomachs to puff in air which I will mention more later. Structurally and colour-wise, they are closely related to Glaucilla marginata.

|

| Ventral Side Anatomy |

Feeding: G atlanticus are carnivores. They will eat venemous Portugese Man O Wars and steal their cnidocysts and use it for themselves on their cerata; toxic blue snails, by-the-wind jellyfish, blue buttons and other sea swallows. They seem to only eat blue things as their main source of prey. Everywhere the Portugese Man O War can be found, the Sea Swallow more or less follows. Due to this, they can be found in tropical and temperate waters.

Digestion/Excretion: The mouth has a sharp radicle which thrusts into the prey. Food goes through a simple gut and through the anus which ultimately removes waste. On most nudibranchs, the anus is on the "forehead." There are digestive glands in the gut that break down the food into enzymes. The mouth has a sharp radicle which thrusts into the prey. Protective hard-barrier discs lining their guts can handle the poisons from the Portugese Man O Wars and such. Somehow, these species have a gas-filled stomach, but nudibranchs are supposed to not have stomachs, so I suspect that these are not "true stomachs." In fact, its stomach is only for swallowing air bubbles so it can float upside down. More on that later.

Circulatory System: Nudibranchs, like abalones, have a two chambered heart and an open circulatory. The blood flows through gaps in the tissue. The blood will pass through a kidney and then the heart again to complete the cycle.

Respiration: Gas exchange takes place in the cerata mostly but also everywhere on the body. Fun fact: Nudibranchs fart too.

Movement: The Sea Swallow has an air sac on what seems to be the dorsal side. It spends its life after the larval stage floating upside down. So while it can wriggle sometimes for movement, it mostly lets itself get carried by the sea currents. It is like a balloon. As such, these sea swallows can get beached very easily, as Florida and Miami and Hawaii may attest.

Defence Mechanisms: The Sea Swallow has cerata which it can detach, spewing a milky substance and wriggling around in hopes to distract a predator. By re-using the defense organisms that it eats, the sea swallow carries all the stingers it steals from its food. After eating jellyfish and other cnidarians, the sea swallow will digest their stinging cells and accumulate them in their cerata and "arms." In this sense, they are very resourceful. They can hurt humans and especially children with their borrowed nematocysts and cnidocysts.

|

| The "Beads" in sexual reproduction |

Reproduction: The Sea Swallow is hermaphroditic. It has a hole on its right side which contains both the male and female reproductive organs. Apparently, the Sea Swallow has a penis that's usually longer its entire body. The female organs produce strings of 10 to 12 eggs. Sometimes, in the thrill of sex, Sea Swallows will try to eat each other's penises.

-bilaterally symmetrical-

(internally and externally)

and

contain three germ layers!

(epi-, meso-, endo-)

AND

they are protosomes!

(spiral cleavage, ventral nerve cord)

They are carnivores that eat, grazing on algae, sponges, anemones, corals, barnacles, and even other nudibranchs. Nudibranchs get their coloring from the food they eat, which helps in camouflage, and some even retain the foul-tasting poisons of their prey and secrete them as a defense against predators.

Nudibranchs are simultaneous hermaphrodites, and can mate with any other mature member of their species. Their lifespan varies widely, with some living less than a month, and others living up to one year.

Anyways,

G. atlanticus are very important species because they eat other dangerous cnidarians like bluebottles. Turtles, fish and sea stars all eat this specific type of sea slug in turn. At the same time, for nudibranchs in general, they may eat unwanted algae that damage coral. The more these soft-bodied mollusks appear in the environment, the healthier the ecosystem. They are also brightly coloured and beautiful. They look like candy, which is why I like them because I like candy. Without the sea swallow, the ocean would be less strange and beautiful. If it went extinct, I think everybody would think that's a shame. Why are nudibranchs so brightly coloured? This is because they will appear toxic to their predators--and sometimes, they are.

I like this species because they are so colourful and epic and regal while being only a few centimeters long. Although they seem so perfect, they are very strange, spending their lives floating upside down and eating each other's penises.

In conclusion, respect the sea swallow.

|

| Australia, East of Grafton in the North |

|

| These were found in Florida. This one is albino. |

|

Locality: Byron bay, washed onshore, N.S.W, 2 feb 2010, beach.

Length: 17 mm. Photographer: steff.

|

SOURCES

http://www.seaslugforum.net/find/22413

http://animalfacts.tumblr.com/post/8646741171/glaucus-atlanticus-is-a-specialist-predator-of

http://www.thecephalopodpage.org/marineinvertebratezoology/glaucusatlanticus.html

http://www.zimbio.com/Fish/articles/2O5IRsBbAKS/Glaucus+atlanticus

http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/nudibranch/